- Home

- Linda Yueh

The Great Economists Page 3

The Great Economists Read online

Page 3

Before we assess what Adam Smith would have made of the attempt, let’s look at why there is a debate over rebalancing the economy. It’s an issue that’s at the forefront in Britain, a country that has one of the largest services sectors among advanced economies. As noted earlier, even though the US was at the epicentre of the 2008 financial crisis it remains the world’s second biggest manufacturer while the UK has slid down the rankings. So Britain’s experience in particular holds potential lessons for other countries.

Changing its economic growth drivers is indeed what Britain set out to do after the 2008 financial crisis. It was termed the ‘March of the Makers’ under the David Cameron government. The UK wants to rebalance its economy towards making things and selling more of its wares overseas. The two are related in the era of globalization, where much of manufacturing output consists of tradable goods. The British government wants to rely less on financial services, given the banking bust of a few years ago, but manufacturing accounts for only around a tenth of the economy, while the services sector accounts for the bulk of national output. Also, Britain, which until recently exported more to Ireland than to the emerging markets dubbed the BRICs (Brazil, Russia, India, China) combined, wants to reorient more towards developing economies and help its companies access the fastest growing markets in the world.

If it is to succeed in this endeavour, it clearly needs to be peddling the right stuff abroad. However, Britain’s trade deficit – the difference between the value of imported and exported goods and services – widened precipitously and hit record highs in the years after 2008. That’s not a great piece of evidence for the rebalancing efforts. The hope was that with sterling having lost about a quarter of its value at one point after the banking crash, a cheaper currency would boost exports in the same way that it did during the early 1990s when the pound left the exchange rate mechanism (ERM) that had tied it to the German Deutschmark. The last time that Britain had a trade surplus was towards the end of that decade in 1997, on the back of a depreciated pound.

Before then, Britain had run a deficit in its current account, the broadest measure of trade that includes financial flows, every year since 1984. Notably, the deficit in goods trade grew after the late 1990s with further deindustrialization. Recall that manufacturing’s contribution to GDP has halved since 1980.

Offsetting part of the overall trade gap is the balance of trade in services, a figure that has been in surplus at least since 1966. Not only is it a long-standing surplus, it is also a large one, typically around 5 per cent of GDP. When the surplus in investment income earned from abroad is included, economic historian Nicholas Crafts points out that the total ‘invisible’ service trade balance has been in surplus for two centuries, since 1816.9

Britain is particularly good at providing services and ranks behind only the US in terms of total service-sector exports globally. These are not just financial services, but a range of business services including legal, accountancy, architecture, design, management consultancy, software and advertising. Also, the trade in services tends to be relatively high valued-added. As competitiveness is derived from quality rather than cost, margins tend to be larger. The fact that UK exports are increasingly represented by high-end manufactures and services might explain why the recent depreciation of sterling has failed to boost trade by as much as was hoped for. Prices still matter, but perhaps not as much as they used to.

One of Britain’s problems is that the global trade in services, which it is particularly good at, has not opened up in the same way as manufacturing. Since the Second World War, the global trade in goods has boomed as multilateral organizations such as the World Trade Organization (WTO) and its predecessors have brought down tariffs and removed restrictive practices. The global trade in services, though, has not been liberalized to the same extent and this hurts Britain. By contrast, where the trade in services has opened up, Britain tends to do well. Higher education is a good example of a UK service industry that successfully serves overseas markets.

Thus, rebalancing the economy and reindustrialization are easier said than done. The recovery may have finally taken hold, but which of these businesses are driving it and which sectors have already recovered? The answers reveal that the recovery is not due to the economy’s ‘rebalancing’.

Manufacturing output as a whole has yet to recover its pre-recession level nearly a decade on. Past recessions have caused major shake-outs in British manufacturing. The industries that survived and prospered in the aftermath have tended to be in more specialized and higher technology niches.

There are pockets of activity which are doing well. The manufacture of alcoholic beverages is above 2008 levels. There are reports that Scottish whisky distillers, who account for a quarter of the UK’s food and beverage exports, are even struggling to keep up with strong worldwide demand.

Britain’s aerospace industry is also faring well. Rolls-Royce, with manufacturing plants in Derby and Bristol, is one of the world’s largest producers of aircraft engines. Farnborough’s BAE Systems is among the largest defence contractors in the world and is building new aircraft carriers.

Although the oil and gas industry is running down, operating expenditure in the oil industry has been growing strongly as it becomes more expensive to extract the remaining ‘harder to get to’ oil. Decommissioning expenditure is also on the rise. Furthermore, British expertise in maintaining extraction equipment, surveying and extracting hydrocarbons from difficult places is in high demand around the world.

Then there’s the housing market. Like manufacturing, construction output has struggled even as the economy as a whole has recovered. Housebuilding is in the doldrums. The number of completed new dwellings has hovered around 150,000 per year; this is less than before the crash and far below the 250,000 per year that many experts argue is needed to meet long-term demand.

The services sector as a whole, however, regained and then exceeded its pre-recession level soon after the crash. But it is a large sector, consisting of a myriad of different activities, and its overall success conceals some internal difficulties. Two sectors to have done badly are, unsurprisingly, banking and government administration. In 2015, the latest year for which annual figures are available, financial services output remained depressed relative to its pre-crisis level despite improvements in the pension and insurance categories. In the public administration and defence sector, output had been falling steadily. The government’s continuing squeeze on public spending is likely to push this lower.

Output in the telecommunications and information technology industries recovered quickly. The growing appetite for new technologies from households and businesses has continued unabated despite the depth of the recession.

Business and professional services, which includes a broad range of business-to-business services including legal, accountancy, management consultancy, architecture, scientific and technical research and consultancy, administrative and support services, human resources, public relations, and so on, contracted sharply during the recession. Compared to the first quarter of 2008, output was 15 per cent lower by the third quarter of 2009. The downturn was short lived, however, and the sector recovered strongly and now exceeds pre-recession levels.

It’s clear, then, that Britain is a services-based economy. Its recovery from the global financial crisis underscores that fact. Although Britain might once have been correctly described as ‘the workshop to the world’ and ‘a nation of shopkeepers’, neither statement has been true for a while.

Manufacturing output and retail sales, once the mainstay of the economy, have been usurped by specialists advising the world how and where to invest, organizing their companies, proposing better product designs, writing contracts, preparing accounts and offering technical advice in the worlds of engineering, IT, architecture and finance. The output of these activities takes the form of blueprints, designs, specifications, recommendations, computer code, ideas, reports, databases and the like. Business activity

increasingly consists of people sitting in front of computer screens and having meetings to appraise projects.

How hard is it to boost productivity and innovation in services? To what extent do policymakers misunderstand the importance of the services sector? What would it mean for economic growth if services were accurately measured?

It’s harder to tailor policies for services than for manufacturing since services are intangible. But, for post-industrial economies, services comprise the bulk of output, so is there much of a choice? Could boosting innovation in services counteract the trend of declining productivity (and therefore stagnant wages) in advanced societies that we will investigate later in the book?

It’s challenging to measure what can be produced in an hour by a professional service such as consultancy compared with the manufacture of a widget. For instance, a London consultancy firm doubled the price of the same report after the economy started to recover. As the price is determined by greater demand, the cost of the report rose even though what was supplied remained the same. It’s hard to separate out the effects of a price increase or quality improvement. No wonder there are challenges in measuring the biggest part of the economy. Some companies are also doing both manufacturing and services. ‘Manu-services’ mean that we also underestimate the evolution of companies like Rolls-Royce, who make more money servicing and maintaining their engines than selling the engines themselves and yet continue to be viewed as a manufacturer rather than a supplier of services.

It’s not only the output of services that’s intangible; the investment is too. Economists are debating whether better measurement of intangible assets would increase GDP. When research and development (R&D) and other intangible investments were included, US GDP was increased by 3 per cent.10 The OECD estimates that intangible investment, including that in human capital, such as education, and software, is as important as investment in tangible machinery and equipment in the UK.11 Since 2014, investment in private R&D has been included in UK GDP. By this approach, UK GDP has been increased by around 1.5 per cent.

Intangible investment is what most firms in the services sector do. They invest in people. Most services companies invest in human capital since that’s their main asset. Innovation comes from people who provide a service better. Even though the coffee machine is the same, we’re aeons away from the tepid brewed coffee that used to be served in cafes as baristas now provide a wide range of espressos and cappuccinos. That intangible investment in their skills to produce a higher quality coffee is hardly measured. If it were, then the puzzle of Britain’s slow productivity growth may be easier to solve if services output is actually higher than measured. Sir Martin Sorrell, the chief executive and founder of WPP, one of the world’s largest advertising companies, says that his company invests twenty-five times more in human capital such as training programmes than physical capital in the UK. He believes that services such as those his firm offers are undervalued as contributors to growth.

The overall challenge is how to measure accurately the largely invisible output and input from companies in the services sector. That consultancy report that doubled in cost counts as doubled output of a service in official statistics. Does a price increase reflect an improved service or simply a higher bill? There are also meetings that could be done away with, but think about the ones where decisions are made and creative processes start flowing. Are meetings a drain on resources or profitable brainstorming sessions? Such imponderables are why it’s difficult to know precisely how much of UK national output is mismeasured. It’s certainly worth trying to do better since this invisible part of the economy generates the most employment.

Better measuring of services output would also affect the country’s balance of payments. The UK has had a stubbornly high trade deficit despite the depreciation of sterling after the 2008 crisis. There is scope to boost exports of tradable services to help pay for the goods that are imported. Among the world’s developing economies there is a growing market for services, including the highly skilled professional variety that Britain specializes in such as education and law. But those same economies also have burgeoning services sectors, so there is competition from those economies to consider if Britain’s position as the world’s second largest exporter of services is to be safeguarded.

Of course, effectively promoting the services sector abroad and supporting it at home depends on its clear quantification. Perhaps it is the difficulty of doing so that has contributed to policymakers focusing on promoting manufacturing. Whatever the reason, rebalancing the British economy hasn’t exactly been successful: services have recovered to pre-crisis levels without too much help or attention from the government, but manufacturing has still to do so nearly a decade after the event.

So, should Britain continue its efforts to rebalance its economy? What would Adam Smith do?

Adam Smith on rebalancing the economy

Adam Smith’s economic system is formulated around three pillars: the division of labour, the price mechanism and the medium of exchange (money). Both the price of goods or services and the wages of those who produce them are dictated by the price mechanism (dubbed by Smith as the ‘invisible hand’). Money has a role set by the market to pay for goods/services, and its supply should not be distorted by the state, for example via mercantilist policies where the aim of trade is to run a surplus of exports over imports and to increase a country’s store of gold and silver.

Let’s delve into these concepts to discern how Smith would view the rebalancing debate.

It is clear that Smith was influenced by the rise of factories. He emphasized the efficiency of a division of labour that allowed for specialization within a production process that comprised several elements. Producing a woollen coat, for example, required wool to be gathered, spun, dyed, woven and tailored. Smith used pin-making to illustrate the benefits of specialization. He observed that ten workers each undertaking their specialized tasks could produce 48,000 pins a day whereas a single person undertaking every task might produce only ten, at most two hundred. In Smith’s view, specialization led nations to become wealthy.

Smith also said that, because earnings could be exchanged for goods, the price of a good and the allocation of resources must be connected. He believed that every good had a ‘natural’ price, which was the cost of producing it. He drew a distinction between that price and the market price, the price consumers would be willing to pay for it. Supply and demand thus govern prices and the ‘invisible hand’ guides the market to an equilibrium.

But Smith was concerned about distortions that could cause the market price to deviate too far from the natural price. In his view, both the state and businesses could distort prices by interfering with market forces, the former by taxation, the latter by keeping prices artificially high. He concluded: ‘Upon the whole … it is by far the best police [government policy] to leave things to their natural course.’12

This approach is known as laissez-faire, although Smith himself never used the term in such a specific way. The concept can be traced to English and Dutch thinkers of the seventeenth century who influenced French merchants during the reign of Louis XIV, a monarch who was keen on mercantilist policies and intervening in the economy. Reportedly, when a French minister asked a merchant what the government could do for him, the merchant replied: ‘Laissez-nous faire, morbleu, laissez-nous faire!’ or ‘Leave us be, dammit, leave us be!’

In terms of Smith’s theories, an outcome of the market mechanism is that it allows self-interest to lead producers and customers to produce and purchase efficiently. As he famously observed: ‘It is not from the benevolence of the butcher, the brewer, or the baker, that we expect our dinner, but from their regard to their own interest. We address ourselves, not to their humanity but to their self-love, and never talk to them of our own necessities but of their advantages.’13

Multiple producers seeking to sell their goods generate competition that moves prices toward an equilibrium. Revenues, in turn,

are used to pay wages for workers (who are also consumers), so the economy benefits from every person in a society acting in their self-interest. Smith was not unaware of the ill consequences of self-interest, remarking that those with poor judgement were subject ‘to anxiety, to fear, and to sorrow; to diseases, to danger, and to death’.14 For the most part, though, an individual’s ambition for ‘[p]ower and riches’15 raised the economic welfare of the society:

[E]very individual … neither intends to promote the public interest, nor knows how much he is promoting it … he intends only his own security; and by directing that industry in such a manner as its produce may be of the greatest value, he intends only his own gain, and he is in this, as in many other cases, led by an invisible hand to promote an end which was no part of his intention.16

That is the premise of Smith’s economic system. His encounter with the French economic movement known as Physiocracy contributed to his views of what it meant for the structure of the economy. Although he disagreed with its emphasis, he built upon its ideas. The Physiocrats valued nature and agriculture, and did not think that manufacturing was productive. In their theories, farming was the sole source of wealth, while everyone else simply consumed what the farmers produced. For Smith, the context was different. Britain was undergoing an industrial revolution whereby manufacturing was increasing both productivity and incomes. Smith even witnessed a nascent consumer revolution as the middle classes began to buy mass-manufactured goods such as clothing.

Thus, Smith pushed these ideas further and crafted an economic system that valued the productive potential of manufacturing and merchants. In book III of The Wealth of Nations, ‘Of the different Progress of Opulence in different Nations’, he argued that, so long as there is no interference, capital will find its way to its most productive use.

After reviewing economic history, Smith argued that one path had led to prosperity: initially agriculture, followed by manufactures and finally foreign trade. Services weren’t valued, as Smith could not have conceived of the technological revolution that would allow output from that sector to be traded as a commodity or a manufactured good on such a huge scale as it is today. For him, for example, a Mozart string quartet could be enjoyed only as a performance, not as a download or on a CD. Had Smith lived today, he might have changed his mind to support some services if they could be traded and had lasting value. That would add another reason as to why he would be concerned about the government rebalancing the economy. At its heart, Smith’s views are centred on an undistorted market.

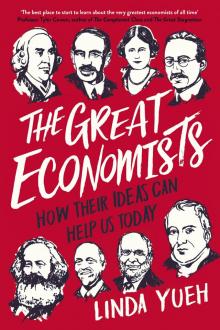

The Great Economists

The Great Economists