- Home

- Linda Yueh

The Great Economists Page 12

The Great Economists Read online

Page 12

His work resonates in the post-2008 crisis period, where the fear of deflation has again returned to the radar of policymakers. Global growth rates have slowed and inflation rates have fallen persistently below the targets of central banks. Throughout history, episodes of deflation are very rare. However, Japan’s ‘lost decades’ since the early 1990s have served as a warning of what might happen in the aftermath of a financial crisis.

Since 2008, advanced countries have struggled to recapture pre-crisis growth trends and inflation rates have slumped around the world, bringing many countries to the brink of deflation. The large build-up in public and private sector debt suggests the global economic situation is ripe for the debt-deflation that Fisher described as the cause of the Great Depression. So, are we at risk of repeating the experiences of the 1930s? And what might Irving Fisher suggest we do about it?

The life and times of Irving Fisher

George Whitefield Fisher, Irving Fisher’s father, was a pastor in the New England Puritan Church. He and his wife, Ella, moved to the First Congregational Church in Saugerties-on-Hudson, New York, in 1865. Fisher was born there two years later.

In 1883 Irving Fisher’s father was taken ill with tuberculosis. Back then this was almost always a death sentence and he was to succumb in June the following year, shortly after Fisher graduated high school. As a child, his skill in mathematics helped him to stand out and he was admitted to Yale University in 1884. This was to be the beginning of a lifelong affiliation with one of America’s foremost universities.

However, he was now the breadwinner of his family. Apart from $500 his father had put aside for him, he knew he would have to both pay his own way at college and support his mother and younger brother, Herbert. As an undergraduate, he tutored mathematics and entered competitions, winning prize money in Latin, Greek and algebra.

His talent was quickly recognized at Yale. After graduating in 1888, he stayed on to do postgraduate study, but his horizons were much broader than mathematics. It is rumoured he had studied every natural and social science course available at Yale, and he began to think of a life in law or economics. Fisher revealed: ‘How much there is I want to do! I always feel that I haven’t time to accomplish what I wish. I want to read much … I want to write a great deal. I want to make money.’7 In 1891 he decided to embark on a PhD in mathematical economics.

His doctoral thesis, titled ‘Mathematical Investigations in the Theory of Value and Prices’, took only one academic year to complete and was in some ways seminal. In it Fisher created a mechanism to compute the prices and quantities of goods in an economy. It was lauded by Nobel laureate Paul Samuelson as the ‘greatest doctoral dissertation in economics ever written’ and was a big step forward in the mathematical treatment of economics.8

The following year he was appointed to the Yale Mathematics Department. Shortly thereafter he married Margaret Hazard, or Margie as the family called her. Margie’s father, Rowland, was a wealthy woollen manufacturer and the ‘patriarch’ of the small town of Peace Dale, Rhode Island. In the 1860s he had formed his own congregational church and invited George Whitefield Fisher to become its pastor. The Fisher family moved there in August 1868, and this is where Irving Fisher grew up, although he and Margie were not childhood friends.

At Yale, Fisher abstained from student frivolity due to his Puritan upbringing. But in the autumn of 1891, at twenty-four years of age, he was invited to a friend’s home for dinner. Margie was there too and, for Fisher, it was love at first sight. Their engagement followed and their wedding took place in June 1893. They spent a fourteen-month honeymoon travelling and working around Europe, a period which also included the birth of the first of their three children.

Fisher returned to Yale in the autumn of 1894 to become an assistant professor in the Mathematics Department. A year later a permanent position arose in the newly established Economics Department and Fisher asked to be considered. After a brief inter-departmental tussle, Economics won out. Fisher was concerned about doing something of practical value, and saw mathematics as too abstract.

At that time, economic thought in US universities was strongly dominated by the German School. Their approach was historically based; theories were acceptable only from those able to demonstrate a thorough grasp of everything that had come before. Fisher, though, was at the vanguard of mathematical economics, which marked him out as a radical and was to ultimately set him apart from his own faculty.

It is perhaps ironic that having fought so hard to get him, the Economics Department was to then have a very marginal relationship with Fisher. He was not impressed with his fellow academics. He thought that they preferred to hide in the classroom rather than apply their subject matter to improving the human condition. Despite his long affiliation to Yale, he was rarely there, taught few classes and did not in general get on well with his colleagues.

In 1898 he was appointed professor and given lifetime tenure on $3,000 per year (about $85,000 in today’s money). Things were looking up. His wife’s family were wealthy, and money left in trust to Margie enabled them to lead a very comfortable life. Their house, at 460 Prospect Street in New Haven, had been a wedding gift from the Hazard family. It was large, fully kitted out and attended to by a number of servants. Fisher could also afford to hire his own secretaries to help him in his academic and campaign work.

But as Fisher was embarking on a successful and happy professional and family life, disaster struck. At the age of thirty he fell seriously ill with TB. He believed that his father had somehow passed on the disease to him and that it had remained dormant until then. It took him three years to beat the illness and recover his strength, but it was to be a life-changing event.

Fisher had revered his father and, although not overtly religious himself, he had inherited his strong moral and Puritan standards. Particularly after the trauma of years of illness, he became obsessed with diet and health. He did not smoke, or drink alcohol, coffee or tea; he never ate chocolate, and only rarely meat. He would arise at 7 a.m. each day and jog around the neighbourhood before a light breakfast. He exercised again around noon in his home gym or yard. Often in the late afternoon he walked or jogged in a park. By 10.30 p.m., he was in bed after some calisthenics. He maintained his fitness regime when he travelled and insisted on his precise diet. On occasion he would even enter hotel kitchens to give specific instructions to the chefs.9

He was to become well known throughout America as a health guru. In 1915 he c0-authored a book, How to Live, setting out basic rules of public hygiene. In total 400,000 copies were sold in the US and it was translated into ten languages. None of his economics writing was as successful. Fisher gave his royalties of $75,000 to the Life Extension Institute, an organization he co-founded two years earlier to promote healthy living and encourage frequent medical check-ups.

Some of his associations were controversial. He was president of the American Eugenics Society and the Eugenics Research Association. His belief in eugenics was based on the maintenance and improvement of the human race. However, he either did not seem to acknowledge or turned a blind eye to the links it had to racial supremacists.

One of his main crusades in life concerned Prohibition. The Eighteenth Amendment to the US Constitution, in effect from 1920, prohibited alcoholic beverages and was in place for thirteen years until it was repealed by the Twenty-First Amendment. He viewed alcohol as a poison that undermined productivity. Drinking alcohol was akin to self-harm. It was in the interest of the economy and society as a whole to abstain. His 1926 book Prohibition at its Worst argued that, even though Prohibition did not work perfectly – he was unhappy with the crime and bootlegging it generated – society was still better off than if alcohol were legalized. The problems were not with Prohibition per se, but because it had been introduced too quickly and before the public has been sufficiently educated in its merits. He tended to support presidential candidates in favour of the 18th Amendment outlawing alcohol and never reconciled himself

to its repeal in 1933.10

His campaigns and activism in public affairs stemmed from his belief that economists should serve the public. And perhaps from a distrust of the political system:

Our society will always remain an unstable and explosive compound as long as political power is vested in the masses and economic power in the classes. In the end one of these powers will rule. Either the plutocracy will buy up the democracy or the democracy will vote away the plutocracy. In the meantime the corrupt politician will thrive as a concealed broker between the two.11

Fisher was also aware of the foibles of economists:

Academic economists, from their very open mindedness, are apt to be carried off, unawares, by the bias of the community in which they live.

Economists whose social world is Wall Street are very apt to take the Wall Street point of view, while economists at state universities situated in farming districts are apt to be partisans of the agricultural interests.12

The Fisher family lived a comfortable life in New Haven. As a professor at Yale, Irving Fisher earned a salary which would have given him a better than middle-class income. In addition, his earnings were supplemented by his many other activities. But he also had expenses, particularly a growing number of staff and secretaries, to whom he would delegate a great deal. But the fact that he lived in a large house with many servants, and that his children were privately educated, was more of a reflection of the wealth he married into. It would not have escaped his notice that his wife’s money was to a great extent maintaining his family’s standard of living.

Fisher always thought that invention would be the key to making a personal fortune. He had tried many times, but his visible index card system was the breakthrough. It was a simple idea. He cut a notch at the bottom of an index card. These could be attached to a metal strip and mounted vertically, horizontally or even on a circular drum. It was a much more efficient way of finding records than flipping through boxes of cards. The concept had come to him in 1910, but he couldn’t find anybody to manufacture the device. Eventually, in 1915, he decided to manufacture it himself, although he had no interest in the day-to-day running of the company, a task he delegated to managers and staff.

By 1919 the Index Visible Company was still struggling to turn a profit, despite a Fisher family investment of over $35,000. But his idea, which he had wisely patented, was practical as well as simple, and as the US economy grew quickly, and record-keeping became vital, it was adopted in companies across the country. As the Roaring Twenties gathered momentum, so did the Index Visible Company’s profits. In the early 1920s he opened an office in New York, and even persuaded the state’s telephone company to adopt the system.

In 1925, he sold his business to the company that was to later merge into Remington Rand. The company and patents were valued at $660,000, plus he received stock in the new company. At the age of fifty-eight, he had at last made a small fortune from his own endeavours. However, turning a small fortune into a large fortune required something extraordinary, and this came courtesy of a rampant bull market in stocks.

Fisher had invested heavily in the stock market, tending to favour start-up companies with innovative products. All proceeds and dividends were reinvested in the rapidly rising market. But he went further. He borrowed money to purchase stocks, a practice known as buying on margin that essentially allows an investor to leverage their portfolio. For example, suppose you buy $10,000 of stock, putting down only $1,000 of your own capital and borrowing the balance. If the market rises by 20 per cent, you are now getting a return of $2,000 (less interest on the $9,000 dollar loan) on your $1,000 investment. By leveraging yourself in this way, it is perfectly possible to generate a large paper fortune very quickly from a strongly rising market, and Fisher was estimated to have accumulated a staggering $10 million in this manner.

The downside to margin buying is revealed when the market falls, and assets become worth less than the amount of debt incurred in purchasing them. Borrowing to invest and being leveraged bring extraordinary gains in the good times, but result in potentially devastating losses should things go awry.

Fisher’s behaviour in the late 1920s in many ways foreshadowed what would happen to the financial sector as a whole nearly a century later. Institutions that are highly leveraged and look sound can suddenly find themselves in a distressed position when the assets they hold become worthless. And in 1929, as the market crashed, Fisher was brought to financial ruin.

He had been a strong advocate of the rising bull market throughout the 1920s. At the end of 1928, he wrote a piece for the New York Herald predicting the continuance of the bull market through 1929. When, at the start of 1929, a growing minority voiced concern about a coming crash, Fisher remained steadfastly confident about the market. There is no doubt he was giving his honest opinion, but unfortunately it was catastrophically misguided. Ironically, he would later blame speculation by others about the value of stocks as the root cause of the Great Crash.

Another irony was that Fisher had pioneered the development of economic data. The Index Number Institute (INI) that he established in 1923 published weekly and monthly indicators of economic activity and prices. As such, Fisher should have been well placed to observe the vulnerabilities and imbalances afflicting the economy in agriculture, housing and manufacturing.

As history tells us, 29 October 1929 or Black Tuesday was not the worst of it. The market would continue to drop for a further three weeks. As the banks started to fail, crash would turn into depression. In 1929 there were 659 bank failures; this number would rise eight-fold during the next three years.

The crash had a devastating impact on the Fisher family finances. His creditors came calling, but all he had to pay them with were stocks that were of little worth. On top of this the US tax authority, the Internal Revenue Service (IRS), was to pursue him over income he had not reported in the boom years.

Once again it was the Hazard family fortune that would provide the lifeline. Fisher’s sister-in-law, Caroline, who was eleven years senior to Margie, had inherited the bulk of the family fortune. The crash had hit her extremely hard, but because her wealth was substantial she remained a rich woman. She lent Fisher stock to use as collateral for more loans to pay off his original creditors. Without this help in buttressing his financial position, it is likely the Fishers would have gone bankrupt in 1930. Over the course of the next decade, he would continuously turn to his sister-in-law to avoid bankruptcy, although Caroline’s main concern was probably the welfare of her younger sister. As the requests for assistance came one after another, she grew tired of dealing with Fisher and even though he was family, she turned over her financial relations with him to her representatives.

In 1935, at the age of sixty-eight, Fisher reached Yale’s compulsory retirement age. Now unable to pay the mortgage on 460 Prospect Street, he sold the house to the university, who allowed him and Margie to remain as life tenants. Eventually, even the rent became too much, and he was obliged to leave the house for the apartment in which he lived his final days.

Would it not have been better for Fisher to declare bankruptcy in 1930? In doing so, he would have lost both his house and his stock portfolio, neither of which was he eager to do. He never stopped believing the economy would turn upwards sooner rather than later, and with it the value of his stocks. He still saw an economic and financial recovery as the most likely solution to his financial troubles. His optimism was impressive. Unfortunately, every time he asserted that a turning point had been reached, things generally turned out to get even worse.

By 1941 Fisher had assets estimated at $244,000 but owed $1.1 million, including almost $1 million to his sister-in-law. This put his net worth in the red to the tune of $870,000. When Caroline Hazard died in March 1945, she forgave the debt in her will.

Irving Fisher’s imprint on economics

In 1903, after returning to Yale upon his recovery from TB, Irving Fisher made some of his most valuable contributions to ec

onomics. He published two books of note: The Nature of Capital and Income in 1906 and The Rate of Interest in 1907. These books, which linked investment and the interest rate, formed the basis for his best-known work in economic theory, The Theory of Interest, published in 1930.

However, perhaps his most influential contribution concerned his Equation of Exchange, which sought to predict what might happen to prices when the money supply changed. It had been known for centuries that there existed a relationship between the amount of money in the economy and prices, commonly known as the Quantity Theory of Money. The long inflationary periods of the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries in Europe had coincided with the discoveries of Brazilian gold and Peruvian silver. Although the relationship had become part of conventional wisdom, until Fisher it had never been formalized or put to practical use.

The essence of the Equation of Exchange, written algebraically as MV = PQ, is that the total amount of money changing hands in the economy is equal to the total value of goods and services sold. On the left-hand side of the equation is the total money supply (M) multiplied by the velocity of circulation (V), a measure of how frequently money circulates in the economy. On the right-hand side is total spending on all the goods and services in the economy, given by the total quantity sold (Q) multiplied by the selling price (P). Although Fisher was not the first to formalize the relationship – MV = PQ had already been written down by the Canadian-American astronomer and mathematician Simon Newcomb in his 1885 Principles of Political Economy13 – it was he who both furnished the theory with a purpose and came up with the statistical methodology to validate it.

Fisher believed that, in the long run, the velocity of circulation is determined by institutional factors such as habits, business practices and systems of payment and credit. He also assumed that the output of the economy was determined by labour and capital; factors which are not related to prices or the money supply. So, if V and Q are fixed, and MV = PQ, there must be a direct association between changes in the money supply (M) and the price level (P). This was the essence of the Quantity Theory of Money. Changes in the money supply will, in the long run, have a direct and proportional impact on the price level. Although the theory imposed a strong prior assumption on the cause and effect, notably the direction of travel from money to prices, it became the central tenet of monetarism, an influential theory that argued that increasing the amount of money in the economy led only to inflation and not real economic growth. It was with this in mind that Milton Friedman was to later say: ‘Inflation is always and everywhere a monetary phenomenon.’14

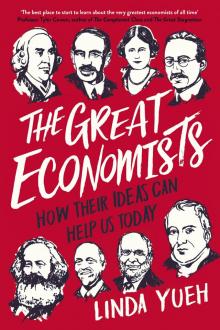

The Great Economists

The Great Economists